Cat and Mouse

Problem Description

A game on an undirected graph is played by two players, Mouse and Cat, who alternate turns.

The graph is given as follows: graph[a] is a list of all nodes b such that ab is an edge of the graph.

The mouse starts at node 1 and goes first, the cat starts at node 2 and goes second, and there is a hole at node 0.

During each player's turn, they must travel along one edge of the graph that meets where they are. For example, if the Mouse is at node 1, it must travel to any node in graph[1].

Additionally, it is not allowed for the Cat to travel to the Hole (node 0).

Then, the game can end in three ways:

- If ever the Cat occupies the same node as the Mouse, the Cat wins.

- If ever the Mouse reaches the Hole, the Mouse wins.

- If ever a position is repeated (i.e., the players are in the same position as a previous turn, and it is the same player's turn to move), the game is a draw.

Given a graph, and assuming both players play optimally, return

- 1 if the mouse wins the game,

- 2 if the cat wins the game, or

- 0 if the game is a draw.

Examples

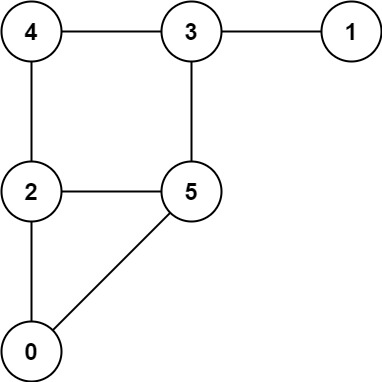

Example 1:

Input: graph = [[2,5],[3],[0,4,5],[1,4,5],[2,3],[0,2,3]]

Output: 0

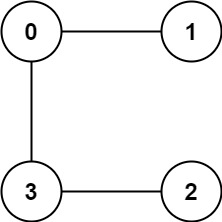

Example 2:

Input: graph = [[1,3],[0],[3],[0,2]]

Output: 1

Constraints

3 <= graph.length <= 501 <= graph[i].length < graph.length0 <= graph[i][j] < graph.lengthgraph[i][j] != igraph[i]is unique.- The mouse and the cat can always move.

Solution for Cat and Mouse

Approach: Minimax / Percolate from Resolved States

Intuition

The state of the game can be represented as (m, c, t) where m is the location of the mouse, c is the location of the cat, and t is 1 if it is the mouse's move, else 2. Let's call these states nodes. These states form a directed graph: the player whose turn it is has various moves which can be considered as outgoing edges from this node to other nodes.

Some of these nodes are already resolved: if the mouse is at the hole (m = 0), then the mouse wins; if the cat is where the mouse is (c = m), then the cat wins. Let's say that nodes will either be colored MOUSE, CAT, or DRAW depending on which player is assured victory.

As in a standard minimax algorithm, the Mouse player will prefer MOUSE nodes first, DRAW nodes second, and CAT nodes last, and the Cat player prefers these nodes in the opposite order.

Algorithm

We will color each node marked DRAW according to the following rule. (We'll suppose the node has node.turn = Mouse: the other case is similar.)

-

("Immediate coloring"): If there is a child that is colored , then this node will also be colored .

-

("Eventual coloring"): If all children are colored , then this node will also be colored .

We will repeatedly do this kind of coloring until no node satisfies the above conditions. To perform this coloring efficiently, we will use a queue and perform a bottom-up percolation:

-

Enqueue any node initially colored (because the Mouse is at the Hole, or the Cat is at the Mouse.)

-

For every node in the queue, for each parent of that node:

-

Do an immediate coloring of parent if you can.

-

If you can't, then decrement the side-count of the number of children marked . If it becomes zero, then do an "eventual coloring" of this parent.

-

All parents that were colored in this manner get enqueued to the queue.

-

Proof of Correctness

Our proof is similar to a proof that minimax works.

Say we cannot color any nodes any more, and say from any node colored or we need at most K moves to win. If say, some node marked is actually a win for Mouse, it must have been with moves. Then, a path along optimal play (that tries to prolong the loss as long as possible) must arrive at a node colored (as eventually the Mouse reaches the Hole.) Thus, there must have been some transition along this path.

If this transition occurred at a node with node.turn = Mouse, then it breaks our immediate coloring rule. If it occured with node.turn = Cat, and all children of node have color , then it breaks our eventual coloring rule. If some child has color , then it breaks our immediate coloring rule. Thus, in this case node will have some child with , which breaks our optimal play assumption, as moving to this child ends the game in moves, whereas moving to the colored neighbor ends the game in moves.

Code in Different Languages

- C++

- Java

- Python

#include <vector>

#include <queue>

#include <unordered_map>

class Solution {

public:

int catMouseGame(std::vector<std::vector<int>>& graph) {

int N = graph.size();

const int DRAW = 0, MOUSE = 1, CAT = 2;

std::vector<std::vector<std::vector<int>>> color(50, std::vector<std::vector<int>>(50, std::vector<int>(3, DRAW)));

std::vector<std::vector<std::vector<int>>> degree(50, std::vector<std::vector<int>>(50, std::vector<int>(3, 0)));

// degree[node] : the number of neutral children of this node

for (int m = 0; m < N; ++m)

for (int c = 0; c < N; ++c) {

degree[m][c][1] = graph[m].size();

degree[m][c][2] = graph[c].size();

for (int x : graph[c]) if (x == 0) {

degree[m][c][2]--;

break;

}

}

// enqueued : all nodes that are colored

std::queue<std::vector<int>> queue;

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i)

for (int t = 1; t <= 2; ++t) {

color[0][i][t] = MOUSE;

queue.push({0, i, t, MOUSE});

if (i > 0) {

color[i][i][t] = CAT;

queue.push({i, i, t, CAT});

}

}

// percolate

while (!queue.empty()) {

// for nodes that are colored :

std::vector<int> node = queue.front();

queue.pop();

int i = node[0], j = node[1], t = node[2], c = node[3];

// for every parent of this node i, j, t :

for (std::vector<int> parent : parents(graph, i, j, t)) {

int i2 = parent[0], j2 = parent[1], t2 = parent[2];

// if this parent is not colored :

if (color[i2][j2][t2] == DRAW) {

// if the parent can make a winning move (ie. mouse to MOUSE), do so

if (t2 == c) {

color[i2][j2][t2] = c;

queue.push({i2, j2, t2, c});

} else {

// else, this parent has degree[parent]--, and enqueue

// if all children of this parent are colored as losing moves

degree[i2][j2][t2]--;

if (degree[i2][j2][t2] == 0) {

color[i2][j2][t2] = 3 - t2;

queue.push({i2, j2, t2, 3 - t2});

}

}

}

}

}

return color[1][2][1];

}

// What nodes could play their turn to

// arrive at node (m, c, t) ?

std::vector<std::vector<int>> parents(std::vector<std::vector<int>>& graph, int m, int c, int t) {

std::vector<std::vector<int>> ans;

if (t == 2) {

for (int m2 : graph[m])

ans.push_back({m2, c, 3-t});

} else {

for (int c2 : graph[c]) if (c2 > 0)

ans.push_back({m, c2, 3-t});

}

return ans;

}

};

class Solution {

public int catMouseGame(int[][] graph) {

int N = graph.length;

final int DRAW = 0, MOUSE = 1, CAT = 2;

int[][][] color = new int[50][50][3];

int[][][] degree = new int[50][50][3];

// degree[node] : the number of neutral children of this node

for (int m = 0; m < N; ++m)

for (int c = 0; c < N; ++c) {

degree[m][c][1] = graph[m].length;

degree[m][c][2] = graph[c].length;

for (int x: graph[c]) if (x == 0) {

degree[m][c][2]--;

break;

}

}

// enqueued : all nodes that are colored

Queue<int[]> queue = new LinkedList();

for (int i = 0; i < N; ++i)

for (int t = 1; t <= 2; ++t) {

color[0][i][t] = MOUSE;

queue.add(new int[]{0, i, t, MOUSE});

if (i > 0) {

color[i][i][t] = CAT;

queue.add(new int[]{i, i, t, CAT});

}

}

// percolate

while (!queue.isEmpty()) {

// for nodes that are colored :

int[] node = queue.remove();

int i = node[0], j = node[1], t = node[2], c = node[3];

// for every parent of this node i, j, t :

for (int[] parent: parents(graph, i, j, t)) {

int i2 = parent[0], j2 = parent[1], t2 = parent[2];

// if this parent is not colored :

if (color[i2][j2][t2] == DRAW) {

// if the parent can make a winning move (ie. mouse to MOUSE), do so

if (t2 == c) {

color[i2][j2][t2] = c;

queue.add(new int[]{i2, j2, t2, c});

} else {

// else, this parent has degree[parent]--, and enqueue

// if all children of this parent are colored as losing moves

degree[i2][j2][t2]--;

if (degree[i2][j2][t2] == 0) {

color[i2][j2][t2] = 3 - t2;

queue.add(new int[]{i2, j2, t2, 3 - t2});

}

}

}

}

}

return color[1][2][1];

}

// What nodes could play their turn to

// arrive at node (m, c, t) ?

public List<int[]> parents(int[][] graph, int m, int c, int t) {

List<int[]> ans = new ArrayList();

if (t == 2) {

for (int m2: graph[m])

ans.add(new int[]{m2, c, 3-t});

} else {

for (int c2: graph[c]) if (c2 > 0)

ans.add(new int[]{m, c2, 3-t});

}

return ans;

}

}

class Solution(object):

def catMouseGame(self, graph):

N = len(graph)

# What nodes could play their turn to

# arrive at node (m, c, t) ?

def parents(m, c, t):

if t == 2:

for m2 in graph[m]:

yield m2, c, 3-t

else:

for c2 in graph[c]:

if c2:

yield m, c2, 3-t

DRAW, MOUSE, CAT = 0, 1, 2

color = collections.defaultdict(int)

# degree[node] : the number of neutral children of this node

degree = {}

for m in xrange(N):

for c in xrange(N):

degree[m,c,1] = len(graph[m])

degree[m,c,2] = len(graph[c]) - (0 in graph[c])

# enqueued : all nodes that are colored

queue = collections.deque([])

for i in xrange(N):

for t in xrange(1, 3):

color[0, i, t] = MOUSE

queue.append((0, i, t, MOUSE))

if i > 0:

color[i, i, t] = CAT

queue.append((i, i, t, CAT))

# percolate

while queue:

# for nodes that are colored :

i, j, t, c = queue.popleft()

# for every parent of this node i, j, t :

for i2, j2, t2 in parents(i, j, t):

# if this parent is not colored :

if color[i2, j2, t2] is DRAW:

# if the parent can make a winning move (ie. mouse to MOUSE), do so

if t2 == c: # winning move

color[i2, j2, t2] = c

queue.append((i2, j2, t2, c))

# else, this parent has degree[parent]--, and enqueue if all children

# of this parent are colored as losing moves

else:

degree[i2, j2, t2] -= 1

if degree[i2, j2, t2] == 0:

color[i2, j2, t2] = 3 - t2

queue.append((i2, j2, t2, 3 - t2))

return color[1, 2, 1]

Complexity Analysis

Time Complexity:

Reason: where N is the number of nodes in the graph. There are states, and each state has an outdegree of N, as there are at most N different moves.

Space Complexity:

Reason:due to the storage requirements of the color and degree arrays, which both have dimensions

[N][N][3].

Video Solution

References

-

LeetCode Problem: Cat and Mouse

-

Solution Link: Cat and Mouse